| |

The information below is to the best of my knowledge and applies to Africa specifically. This page is updated as my journey continues and my knowledge widens.

When I prepared for my first overland journey by motorcycle I searched the Internet and books for information on specific topics that I was unsure about. There is no lack of information. The difficulty lie in finding specific information for my specific needs. Many times the information is provided by experts and experts tend to miss the most basic aspects of the subject they inform about. For them it is too obvious to even mention. As I keep gaining experience in motorcycle traveling, I share a selection of my new found knowledge here. This is my take on things.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

The wise and the experienced debate whether a small and light bike is better than a large and heavy bike. I have not seen an unanimous conclusion in this debate so I'm pretty sure there is none. I'm much too inexperienced to give any advice. The only thing I can share are thoughts around my own choice of bike.

My choice fell on a Honda Africa Twin, 750cc. It is a heavy bike. It weighs more than 200 kg. With me, my luggage and a full tank of fuel the total weight is over 400 kg. It is a 2003 model which was the last year Honda made the classic Africa Twin so I figured most engineering faults would have been corrected. It is also a bike with a 1990's technology which means it is fairly basic and does not have fancy electronic and mechanical features, a fact that would improve my prospects of getting it fixed by a local mechanic in case of a break down. (I have met a few BMW GS owners that have envied me this.)

The most

crucial aspect of choosing the Africa Twin was that every single adventure bike review I read had it among its' top choices of bikes. The Africa Twin is renown for its' reliability, a reputation that I so far have had no reason to contest.

Some people say that you can't do any serious off-road driving with a heavy bike. Very true, but to do any serious off-road driving on any bike you would first of all need experience, which I am lacking. Furthermore, most overlanders carry a lot of luggage which make even a light bike too heavy for serious off-roading. Serious off-road driving is usually done on shorter trips where the luggage is left at the hotel while the off-roader is out playing with his light motocross bike.

But this does not mean that overlanders don't go off-road. As I have come to experience, off-road is where the adventure really starts. This type of off-road driving is not so much playing around, for me it is more a matter of getting me, my bike and my luggage through rough roads and trails in order to experience remote areas and wonderful nature. For this purpose a bike as heavy as the Africa Twin is quite all-right. At times I wish the bike would have been lighter but to make any significant difference it would have to be significantly lighter which means a significantly different bike and a significantly different driving experience.

Besides, I do the big bulk of driving on major roads (which can be oh so rough) as off-road driving is very time consuming as well as tiresome both for body and mind. I do shorter (a day or two) off-road sections here and there when the adventure mood grips me and the weather permits.

When I first loaded up the bike with all the luggage (this was only a couple of days before departure) I got really concerned. It seemed so heavy and so instable. I was seriously questioning my sanity. But, as with most things, I soon got used to it and eventually I found myself on small trails that I had thought impossible to navigate on this bike prior to this trip.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Leading up to this trip I pondered a lot weather I should fit a larger fuel tank on the bike. Most experts advised against it reasoning that it would only add weight to the bike and the original 23 liter tank would be enough, apart from a few stretches where I had to add an extra jerry can to get through. (Those stretches being in the desert areas.) Another reason against a big tank, apart from the substantial cost of cause, is that it will alter the handling of the bike.

Leading up to this trip I pondered a lot weather I should fit a larger fuel tank on the bike. Most experts advised against it reasoning that it would only add weight to the bike and the original 23 liter tank would be enough, apart from a few stretches where I had to add an extra jerry can to get through. (Those stretches being in the desert areas.) Another reason against a big tank, apart from the substantial cost of cause, is that it will alter the handling of the bike.

In the end I did fit a huge 43 liter Touratech tank and I have not regretted it for a second. In my mind I do not want to have less than 10 liters in the tank at any time as I would be worrying about running out of fuel and that is a worry I can do without. With the big tank I fill it up in the morning and no matter how far I drive I do not need a gas station for the rest of the day. Piece of mind.

A full tank will get me at least 750 km before I have to switch to the reserve that will get me another 100 km.

After a couple of years in Africa my opinion is that a 43 liter tank is a bit excessive. 35 liters would be optimal. This would take you safely through all desert areas unless you venture out in unpaved territory but again, you don't want a bigger tank when going on rough roads.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

I made quite a few modifications to my bike before I set out on this journey. These are the ones I appreciate the most:

The original Honda saddle has a bit to wish for and the Touratech comfort saddle has made my journey less "a pain in the ass".

I have dropped the bike several times and the crash bars together with the handle bar protections and the pack boxes have saved the bike from any serious damage. Indispensable.

My handle bar protections are made from impact resistant plastic that is said not to brake if the bike is dropped (not necessarily true though). Metal ones may buckle but the plastic ones retain their original shape.

A lockable GPS holder is great. I don't have to remove the GPS every time I leave the bike for a short while. I have fitted a power cable that switch the GPS on and off with the ignition key. A small feature but very convenient.

I have also fitted a 12V outlet of the type you find in cars. I use this with my mini air compressor and it could be used with any device with a 12V fitting.

The AT is fitted with a proper bash plate from the factory, otherwise this would be a good investment.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

There are different types of tyres for different types of surfaces. Let's make it easy and divide them into three categories. There are different types of tyres for different types of surfaces. Let's make it easy and divide them into three categories.

1. Road tyres (Best on paved surfaces but work well on dry dirt roads)

2. On/Off-road tyres (50/50-tyres. Work well in all conditions, dry, wet, hard surface, soft surface)

3. Off-road tyres (Knobblies, work best on real off-road but wears very fast, less grip on paved roads)

I would expect that people who use full off-road tyres would not be reading this text in the first place so if you are reading this, full off-road tyres is probably not for you. They wear much too quickly for a long overland journey. They would be excellent for a two-month trip to Morocco doing a lot of piste and technical driving.

Choosing between road tyres and 50/50 tyres requires a little more thought. If you know for sure that dirt roads are a rarity on your destination, road tyres may be a possibility. Otherwise I would chose a 50/50 tyre as they are durable enough and give you more freedom and flexibility. Note that in Africa any road can turn nasty even if it looks reliable on the map and some of the worst conditions are found at extensive road works which can take place anywhere.

My choice fell on Heidenau K60 Scout and although I'm far from an expert, I can definitely recommend these tyres for anyone perhaps except die-hard off-roaders. The K60's are well known for their durability. I rode a K60 Scout front tyre from Morocco to Durban, South Africa, a distance of 35 000 km. The rear tyre can do at least 25 000 km. It should be said that I drive conservatively and rarely over 100 km/h. This has importance for how long the tyres will last.

More tyre information can be found here.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

As I had 6 200 km to drive in Europe before getting onto African soil I used the road tyres that were already on the bike for this stage. I then changed to more suitable tyres in Algeciras, just before crossing the Gibraltar strait. An excellent place for this is the small workshop specializing in motorcycle tyres called Motorrodar in Algeciras.

Tyres for big bikes are not generally available in Africa outside South Africa and Windhoek, Namibia as most locals ride small 150 cc bikes. I carried one spare rear tyre through West Africa which adds to the eight but wasn't a big deal. I fitted new tyres in Durban, SA which was very simple. Any motorcycle dealer in South Africa can order most types of tyres within 48 hours at almost internet cost.

As I have had no immediate need for tyres I have not done any local research into this. The only indication that there could be big bike tyres at hand, or at least a place that could order them, is when I have seen locals on big bikes on the roads.

In West Africa those places are: Dakar (Senegal), Accra (Ghana), Calabár (Nigeria), Yaoundé and Douala (Cameroon).

Other places in this category that I have not visited would be; Abidjan (Ivory Coast), Kumasi (Ghana), Lagos (Nigeria).

In East Africa the best bet would probably be Nairobi, Kenya but don't count on it.

One thing worth trying would be to ask the local police, which sometimes are riding big bikes, where they get their tyres from. Usually the police is keen for some bike talk if approached at a suitable time.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Before departure, my inexperienced mind thought that I would be kneeling beside the road fixing flat tyres more often than not. After twenty months and almost 60 000 km I have only had two punctures, both on the rear tyre.

I use inner tubes in my tyres and I carry one spare tube for each wheel so I do not have to do the actual repair along the road. I can "just" replace the tube and do the repair in peace and quiet when I reach a hotel.

Changing an inner tube or repairing a puncture along a busy road can be a stressful task at the least. Therefore did I make a that I laminated and keep in the bag for my mini air compressor. It is based on the excellent instructional DVD, that is part of the Achievable Dream DVD series by Horizons Unlimited. On the back side I have all the technical specifications for my bike; tyre sizes, sprocket sizes, spark plug specs, bulb types, etc. It can be downloaded it here.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Dropping the bike does not mean crashing. Dropping the bike is done at a standstill or at very low speed, normally when navigating tricky terrain or parking in tight spaces. An overland journey will not be completed without a few drops so crash bars and handle bar protections are good things to have mounted on the bike.

Before this trip I had only dropped the bike once (in a parking lot, very embarrassing) and I was not able to lift it back up on my own. The three first times when I dropped it on this trip (once in deep sand, once the side stand sunk into soil that got soft after someone had watered the trees and the bike fell over, once when making a sharp turn when parking) there were people around that helped me lift the bike. On the next two occasions I was alone but still managed to get the bike up after removing some of the luggage.

The correct way to lift a fallen bike is to turn your back to the bike, put your butt to the saddle, get a steady grip with both hands (luggage rack and handle bar) and start taking small steps with your feet. The idea is to use the big leg muscles rather than breaking your back. It does work if the ground is flat. If the bike would fall in a deep rut or other tricky place, there is no way I could get it back up by myself. This is the downside with a heavy bike but there is generally people nearby to give a helping hand.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Before this trip I made a complete service of the bike. I also added quite a bit of custom parts and did some rust removal and painting. I noted down every tool and tool size that I used during this work, compared it to the set of tools that comes with the bike and from that list I compiled a suitable set of traveling tools. I carry more tools than I need and I surely lack a tool or two but this was the best I could do with my limited experience.

My strategy was to familiarize myself with most external parts of the bike so I could do the most common repair- and service work myself. Anything inside the engine and gearbox I left to Providence and the African mechanics.

A list of the tools I carry can be found here.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

I set the start date for this journey to coincide with the cooler months in the Sahara, so I have managed to avoid the really hot temperatures. Even so, I have driven in 40°C and as long as I am moving (even at slow speed) I'm quite comfortable but as soon as I stop, I want to get out of the riding gear as soon as possible.

I wear a proper motorcycle jacket (Amarillo) and pants (Pezzo) by the German manufacturer Held which I am really happy with. They are lightweight and highly wind permeable and have the proper protections. They are especially designed for warm weather riding. They are not rain proof. Underneath I wear a very thin sports t-shirt. I wear a full face helmet (Shoei Multitech) with a flip-open visor. It is black but I don't think a dark color attracts noticeably more heat than a light colored one. Normally I ride with the visor open wearing tight fitting sun glasses but the visor comes in handy when I want to shut out dust, exhaust fumes and rain. In warm weather it is too hot having it closed for longer periods. On my feet I was initially wearing lightweight motorcycle boots by XTC. When they were worn out I used my hiking boots.

I put on a rain jacket (Arso) and rain pants (Sarone) also by Held. They are designed to be used with the Amarillo jacket and Pezzo pants. I usually wear them on the outside but they can also be worn underneath. Sure, it is a bit of a hassle to put them on but the truth is, I have not had to use them very often and wearing a fully rain proof outfit would be too hot in many parts of Africa.

I wear a light weight fleece jacket and if necessary also a wind resistant vest. That is all of warm clothes I have needed. In rain and cold temperatures I put on my motorcycle gloves. Even if they are summer gloves I find them too hot to wear in warm weather. When I got to Windhoek I bought a pair of regular motocross gloves which are perfect for African weather. They may not protect your knuckles but they have protective material in the palms which is indispensable when riding a heavy bike. Only a couple of times have I been really cold of my hands and only at high altitude (above 2000 m).

A good thing about having separate rain gear is that I can use it also off the bike.

West Africa is generally hotter than East Africa (south of Sudan). To my surprise, I was very seldom hot riding in East Africa as the altitude is generally higher. Botswana, Namibia and desert areas of South Africa can be very hot in summer.

Check this page out for an overview of rain patterns and average temperatures in Africa.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

This was something I was concerned about before this trip but I soon realized there was little cause for this concern. Almost all hotels, guest houses and lodges (even the very cheap ones) have a walled in courtyard with a dedicated parking space where the motorcycle is as safe as it gets. Many times they have a guard on duty. Only a few times, in big cities, have I had to look for another option where the hotel didn't have safe parking. A handful of times, also in big cities, have parking been arranged by the hotel staff in the hotel vestibule or in a hallway. It usually requires getting the bike up one or two steps. Needless to say, this will not be done in fancy hotels. One time, in Rabat, I parked in a public parking garage - very expensive. In Dakar I was allowed by the guard to park outside the galleria below the hotel during the day and put the bike inside the gates during the night. I paid a small token for this but peace of mind is definitely worth a little money.

Official camping sites are usually as safe as anything.

I use a sturdy chain lock that goes through the back wheel while the steering lock keeps the front wheel in check. It would require a handful of men to cart the bike off so I'm not especially worried about it being stolen. Besides, I have had a liter bottle of engine oil and a can of chain lube strapped on one of the pack boxes (which I normally leave locked on the bike) for almost two years without them getting nicked. My experience of Africa is that it is no more unsafe than any other part of the world, including Europe. During the second half of this trip I have hardly used the chain lock as I have come to think it is really not needed. I could certainly do without the weight of it. At certain times it has been useful.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

- 2 passports (I applied for a second passport before I left because of the requirements of certain countries (primarily DRC and Angola) that you have to apply for visas in your home country and that I may have to send one of them home to Sweden to get the visas.

- 1 year international driving license.

- 3 year international driving license.

- Motorcycle registration document (a laminated copy).

- Driving license (plus a few laminated copies).

- Yellow fever certificate. This is a little yellow booklet issued by the immunization center in my home town. It verifies that I am vaccinated against yellow fever which is required to enter, as well as applying for visas to, certain countries.

- Motorcycle insurance valid for Europe and Morocco (plus a green card).

- Plenty of passport photos for visa applications (need to be replenished along the way).

- Travel insurance.

I have digital copies of all documents on my computer, on a thumb stick and with family back home (a cloud account would work). Photocopies of passports are needed when applying for most visas. Sometimes a copy of a specific visa is needed as well but this is handled when the need occurs. Photocopy-shops are abundant, especially in embassy areas.

- Plenty of photocopies of passport main page. These are needed at most visa applications.

- Fiche. This little home made document is very handy in Western Sahara and Mauritania. See #1 and #2 in the "In Detail" of the Beyond Borders section for details.

|

|

| |

Applying for a visa can be quick and efficient or it can be extremely slow and very cumbersome, It all depends on which country you are applying for and at what embassy/consulate you're at. It may also depend on the mood of the day of the person you are dealing with. One thing is true for all of them: It is never any fun.

In my experience there are seldom any queues to talk about at the various embassies and consulates in Africa (like it sometimes is in Asia). Embassies and consulates tend to relocate on a regular basis so don't expect to find it where your guidebook has it marked, or where I have it marked in this information for that matter.

Generally, the most difficult visas are found in countries between Ivory Coast and Angola on the western coast and Ethiopia and Sudan in East Africa. The easiest area is in the south and south east of Africa where you either don't need a visa or you get it at the border.

The best time to visit an embassy or consulate is in the beginning of the week and first thing in the morning. Some places issue a visa while you wait but most require that you come back in the afternoon, the next day or up to seven working days later. Avoiding the "waiting weekend" is a skill mastered by only the most intrepid visa applicants.

As a traveler you will want to apply for a tourist visa. Normal visas, working visas and long term visas all have stricter requirements. Tourist visas usually come with a duration of 1, 2 or 3 months and 1, 2 or multiple entries. The more, the costlier. If the handling time is several working days, there may be an express service which also cost more (up to double the normal cost). A cheap visa cost 30-60 €, an expensive visa can cost up to 150 €.

An important factor to look out for is the start date of the visa. The visa can start at the date when it is issued. Sometimes it is possible to request a start date in the application form so the visa starts close to when entering the country.

Normally you need at least a photo copy of your passport (the two pages with the main information) and one or several photos. Many embassies and consulates have further requirements and there is no end to what they can put in your way to obstruct the application process.

These are some of the most common requirements:

- Photo copy of passport main pages

- Color photo (1-4)

- Yellow fever vaccination card + photo copy

- Hotel reservation

Normally a one day reservation of any hotel you can find on the internet booking sites will do. Preferably use a booking site with no reservation fees. You can cancel the booking right after you have received your visa. The reservation will most likely not be verified. As long as the embassy staff gets a complete set of documents they are usually content. In some cases I have "photoshoped" a hotel reservation based on a real reservation.

Other requirements that may apply are:

- Photo copy of the visa of the country where you apply for the visa

- Photo copy of entry stamp of the country where you apply for the visa

- Copy of travel insurance

In very rare cases the following requirements may apply:

- List of complete itinerary signed by the applicants' consul in the country where the visa is applied for

- Letter of Invitation (LOI) from your embassy.

- Letter of invitation (LOI) from either a hotel or a travel agent within the visa issuing country. Few countries have this requirement and you usually need the help of a visa agent to obtain a LOI. Sometimes a hotel in the country can assist with this.

At the embassy or consulate you will also have to fill out an application form or two.

Many times there are a photo copy places near the embassies so if you forgot to make copies or have run out of photos, there is usually a solution around the corner.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Quite a few African countries demand that you apply for your visa in your home country. This is a real pain in the ass traveling through west and central Africa. In most cases, for example Ghana and Nigeria, you get around this obstacle by applying for the visa at the right embassy where they will overlook this official requirement. I got my Ghana visa in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) which is currently (2015) a reliable place to get it. In Bamako they do not issue Ghana visas to non residents of Mali. For Nigeria I got my visa in Ouagadougou as well but I might just have been lucky, although I've heard of others being successful there. Otherwise Accra is generally considered the best place to get a Nigerian visa (if coming from the north that is).

For Congo Kinshasa (DRC) and Angola the "applying in your home country" requirement is not that easy to get around. You may be able to apply for visas in neighboring countries but those visas will in most cases be refused at the border crossings. A fellow biker applied for a visa for Angola in the border town of Matadi. The only visa he could get was a five day transit visa. He was told that it could be extended in Luanda but it could not, so he had to dash through this large country with a 100 USD per day penalty fee hanging over him. He overstayed his visa by two days and managed to get away with paying "only" 100 USD in penalty.

Two reasons made me bite the bullet and send one of my two passport to a visa agent in Stockholm to get visas for Congo Kinshasa and Angola. (This is the main reason why I carry two passports on this trip):

- It was the rainy season and I didn't want to rely on small border crossings that might have been terribly muddy.

- I have heard and read about various travelers praising the beauty of Angola and at the same time lamented that they had to rush through the country on a short term visa.

Having a visa agent doing the leg work is always easier than doing it yourself. They know the requirements and they have the proper contacts. I sent my passport by DHL express to Stockholm from Yaoundé (Cameroon). I just walked into a very small DHL agent next to my hotel. They said it would take three days for the passport to get to Stockholm and it did indeed take three days. The visa requirements were all manageable for both DRC and Angola. The plan was to have the passport sent to another DHL representative in Brazzaville but in the meantime my journey was interrupted by an accident. The whole exercise was prohibitively expensive though. Find details here.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

The VTE (Visa Touristique Entente) is a single visa that is valid for five countries in West Africa namely:. This sounds like a dream for the weary visa hunter but there are a few drawbacks.

You cannot apply for it outside the five countries (at least not in the neighboring countries), so in order to get this visa you must first get a visa for any of the five countries and then apply for the VTE once inside the VTE area.

The VTE is valid for 60 days with a single entry to each of the five countries. The visa you obtain for the first country must be valid for the whole duration of the VTE, i.e. 60 days from when you apply for the VTE. This means that the visa for the first country must be at least a three month visa. If you show up at the VTE application place with a visa that will expire within 60 days they will not issue a VTE.

To the best of my knowledge the VTE will expire once you have left the five countries for which it is valid and as Ghana sits right in between, it is not an optimal situation.

I was able to enter Ivory Coast from Ghana on the VTE at a small border crossing but I was refused entry into Togo from Ghana on the VTE at a large border crossing. (Instead I was issued a 7 day Togo visa at the border). I was told that they refused the VTE, not only because I came from Ghana

but because I had already left the VTE area. I later entered Benin from Togo at a small border crossing on the VTE without problems.

To make things more difficult, it seems that the VTE is not regularly issued in all five countries. The VTE is definitely issued in Ouagadougou and reports say that it is also issued in Niamey, Niger. For the other three countries I have no information. I applied in Ouagadougou which seems to be the easiest place to get it. You do not apply for it at any embassy but need to go to Direction Generale de la Police Nationale (N12° 21.629' W1° 32.451') southwest of the city center. Normally it takes 3 working days to issue the VTE but I got it in 2 days after some negotiations. The cost is 25 000 CFA (40 €). You need two photos.

A good reason to get the VTE in Ouagadougou is if you are planning to visit Ivory Coast next. The Ivory Coast visa is both more difficult and more expensive to obtain than the VTE. It is possible to get an Ivory Coast visa in Bamako, Mali but it is a bit of a hassle.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Three East African countries have joined the EATV (East Africa Tourist Visa) initiative: . There have been talks for years that Tanzania and Burundi also would join but this is not likely to happen in the near future. Burundi has internal, political issues which is always a sure sign of visa restrictions. The Tanzanian internal visa apparatus is probably too lucrative for corrupt pockets to be done away with.

So for now, travelers have to be content with one single visa for Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda which is at least one small step forward to promote tourism. There are tales on the internet of difficulties to obtain the EATV at different borders but this may be stories of the past because I had no problems at all obtaining one on entering Rwanda at the Rusumo border crossing. The immigrations officers knew exactly what I was talking about and it was a formality to have the visa issued.

The cost was 100 USD for a 3 month multiple entry visa. I could even visit countries outside the EATV zone (Burundi) and then return on the same visa.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

NOTE: that I am traveling on a Honda 750 Africa Twin. Smaller bikes, below 200 cc (or thereabout), like the ones the locals are using, may be exempted from

some of the bureaucracy that the large bikes have to put up with, but I wouldn't count on it.

In this documentation I'm using the term (TIP) to describe the document issued at border crossings and which permits my motorcycle into the country without paying import tax.

In French it is called:

or

In Portuguese it is called:

A TIP is issued if you do not have a Carnet de Passages en Douane (CPD or Carnet in short).notno matter what some border scammers might tell you.

If you do not have a carnet. Police and border officials will ask for it both when crossing the border and at police/customs checkpoints within the country (mostly in West Africa). At times it may seem like the TIP isn't checked or taken very seriously but my advice is to always make sure to obtain one when entering a country and always return it when leaving. Sometimes you can pass through a country totally ignoring the TIP (but they are few, trust your intuition) at other times you may end up at central customs offices, having to endure hours of queuing and paying fines in order to sort out a skipped or outdated TIP. It's not worth it.

, not at the immigration post. . It consists of a piece of paper on which will be noted the registration details of the motorcycle. The registration document (or a copy thereof) is needed when issuing the TIP.

is typically around 8 € per country in West Africa and 20 € in East Africa. South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland do not require a TIP. If you are visiting a country several times you will normally be issued a new TIP, and pay a new fee, for each visit.

varies widely. Sometimes you only get a couple of days, other times you get a whole month or even more. Before the TIP expires, you have to either leave the country or visit a customs office to get it extended.

at most customs offices within a country. It doesn't have to be in the capital. In Senegal, for example, it can be extended 2x15 days, in Guinea-Bissau 3x15 days. After that you need to either exit the country and get a new TIP or get the bike registered in the country.

you should return the TIP at the customs post no matter how pointless it may seem. Many times they don't even check the TIP when you return it so if it has passed the expiration date with a few days it may not be a big deal. At other times, in countries which have a computerized system, it is essential to get the TIP cleared when exiting the country, especially if you intend to return to that country in the future.

At a checkpoint within the country they might not look so kindly upon an invalid TIP, which could result in a fine and an instruction to get it extended. This is mostly an issue in West Africa.

When the TIP is returned upon exiting a country the idea is that the information that your vehicle has left the country will be registered in a central database.

When my TIP is thrown in a huge pile of other documents it is sometimes hard to see this happening. But it is important that the TIP is returned otherwise, upon your next visit, customs will think that you left your vehicle in the country on your previous trip (provided that they have a computer system and are hooked up to it) which can be troublesome. One traveler I met in Bamako, Mali had his car impounded at the border when entering from Mauritania. He had sold his car in Mali on a previous trip and the customs officers saw this in their computer system.

When the TIP is issued you may be asked at what border post you will exit the country. They say that the reason for this is so they can track your TIP, especially if they don't have a computerized system.

- All except the ones below

- Nigeria

- Gabon

- Angola (but only at the border I entered)

- South Africa

- Lesotho

- Swaziland

Why not use a Carnet as it will not cost you anything at the borders. True, If you have a Carnet you do not pay anything when crossing borders but it does cost

a substantial amount of money to have it issued and furthermore you need to deposit a large amount of money (sometimes equal to the value of the bike) which is only returned if you return with your bike to your home country together with an entry stamp. There are ways around the deposit by bank guarantees but without a carnet there are no strings attached. If you crash it, if it is destroyed in a fire or even if you sell it, no one will ask for any paperwork when you get back home. To me it is a matter of peace of mind.

I'm counting on paying less for all the TIP's needed for the entire trip than I would pay for having a Carnet issued. A Carnet issued in Sweden is only valid for one year and 25 border crossings. As I'm traveling for longer than that I would have to have it renewed along the road

with all the trouble that comes with it.

Some countries prefer and encourage the use of a Carnet. This may mean that issuing a TIP can be costly and complicated. Countries included in this category are so far:

- Ghana

- Ivory Coast (but only because they had internal problems issuing a TIP)

People have certainly done it before me and I do not carry a Carnet. It is said that some countries require a Carnet but people have evidently entered those countries without it so I am sure it can be done. Time will tell and I will keep you posted as the journey proceeds.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

A Carnet de Passages en Douane (CPD or Carnet for short) is an internationally recognized set of documents that will let your vehicle into a foreign country without paying import tax. Basically it get stamped by customs when entering a country and it get stamped again when exiting the country to ensure that the vehicle has not been left behind (i.e. illegally sold). When using a carnet most borders are crossed without cost. Getting the stamps should be a formality.

I chose to travel without a carnet for different reasons:

- First of all, a carnet is valid for twelve months only. As I am traveling longer than that I would need to have it renewed along the way which would burden me with more bureaucratic hassle than I need. One carnet is good for 25 countries and I'm visiting more countries than that on this trip.

- Secondly, a carnet is expensive to obtain. In Sweden the issuance of carnets is handled by the motorizing association called Motormännen and they charge about 500 € for a one year, 25 countries carnet. Only one year at a time can be issued.

- Thirdly, I would be required to leave a bond as a guarantee for the carnet. For my bike this bond would be about 50 000 SEK (5 500 €) and would only be returned by proof of the correct entry stamp into Sweden in the carnet. An alternative to the bond is to arrange a bank guarantee which would cost 30 € extra plus whatever the bank is charging.

To keep a care free mind and save some money I decided against a carnet. Instead, I am required to buy a Temporary Import Permit (TIP) for most countries that I visit. See above.

As I am approaching one year on the road I can happily say that I made the right choice (so far that is). For this first year I have paid less than 200 € in TIP fees and I have not had to worry about any bond in case the bike would be stolen, crashed or destroyed by fire. Sure, a couple of countries (Ghana and to some extent Ivory Coast) have given me unreasonable trouble because I had no carnet but so far there has been a solution for each country.

During 2016, several motor organizations (RAC in Great Britain, Motormännen in Sweden) have stopped issuing carnets altogether. You can get a carnet outside your home country.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

The short answer is: Well, it depends on where you are traveling.

European vehicle insurances may be valid in some of the African countries along the Mediterranean coast. My Swedish insurance was valid in Morocco including West Sahara. In that case you may need a "green card" as proof of insurance. It is issued by the insurance company. I was never asked for the green card in Morocco.

I was asked for an insurance document, either at border crossings and/or at checkpoints along the roads, when traveling through: Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali and Burkina Faso.

I was not asked for an insurance document at any point when traveling through:

Ivory Coast,

Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria. This doesn't necessarily mean it is not required.

In the countries that do require insurance you need a document that looks convincing and that has not expired. This document doesn't necessarily need to be entirely authentic or extensive, a small slip of convincing paperwork will do.

In general I would say that the insurance is good to have in the countries that require it. If for no other reason, to avoid putting yourself at the mercy of the occasional official that want to take advantage of any discrepancy in your paperwork. At a few borders you will not be let through without insurance (mainly Mauritania and Senegal).

In countries where it is required: The insurance document is many times, but not always, checked by customs and police when crossing borders. It is sometimes also checked at random road checkpoints within countries. It may also be checked when extending the TIP.

However, it is rarely scrutinized and the validity of my insurance was never put to the test. In theory I guess they could call the insurance company and have it verified but I would like to see the official who makes the effort.

When traveling through Guinea-Bissau I showed my multi-country insurance document several times and it was accepted each time. Later I discovered that Guinea-Bissau was not among the countries listed in small letters on the front page.

I was sometimes asked for insurance at the border but never at road checkpoints. In some of the southern countries like Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia one must pay a "border fee" which includes vehicle insurance in addition to various taxes (carbon tax, road tax). I'm not sure if you can avoid the insurance fee if you already have insurance. I'm not sure if vehicle insurance is included in the Namibian "Cross Border Charge Permit".

Showing up at a border without insurance is never a problem. If insurance is required there will be someone selling it within or just after exiting the border area. Typically, at the last border stop before being let into the country your documents will be checked and if you have no insurance you will be directed to the insurance sales place.

At small border crossings there may not be anyone selling insurance. My experience is that if insurance is required at a border, there will be someone selling it. It is extremely unlikely that you would be refused entry into a country because you don't have insurance. At the most you will be told to go get one at the nearest city.

Insurance can sometimes be bought within or just after exiting border areas. Any insurance company within a country will sell you their products (except in Ghana).

as this is not permitted for foreign registered vehicles in accordance with the law. Ghana is an example of this, the only example I came across.

Presumably, at the insurance sales places at borders, the price is bound to be inflated.

At the Guerguarat-Nouadhibou crossing between Morocco and Mauritania I paid 30 € for 30 days.

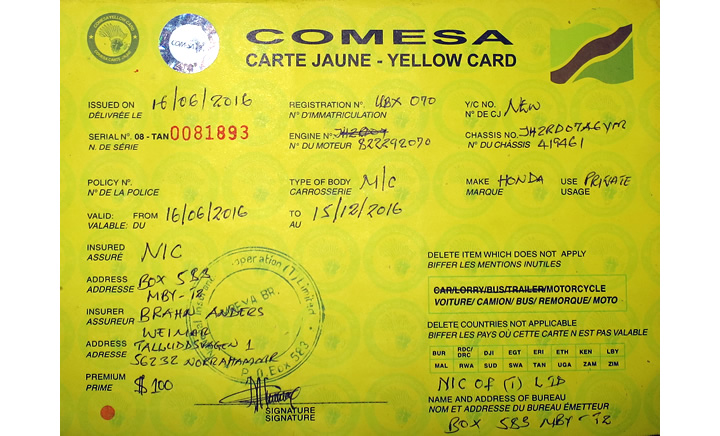

On the other hand, at the Diama border crossing between Mauritania and Senegal I paid 30 € for three months. I paid 100 USD for the COMESA insurance which I negotiated to be valid for 6 months. No matter what, the insurance cost for all of Africa will not break your budget.

One generally hear people saying that the insurance is not worth the paper it is written on and that there is little hope of getting any money from a claim. I have no knowledge about this but I treat it as a document to show officials and nothing more. The insurances you buy will probably only be third party anyways.

Just after the Diama border crossing between Mauritania and Senegal there was a lone woman selling insurances from a company called CGA (Compagnie Generale D'assurances). It is valid in most "CFA-countries" including: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, CAR, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Mali, Senegal, Niger, Togo as well as traversing of The Gambia. It cost 15 000 / 17 000 / 18 000 CFA (25 / 28 / 30 €) for 1 / 2 / 3 months. At the time I was not sure if it was a legitimate insurance. Later I regretted that I didn't buy a 6 month insurance for only a few Euros more. The lady sold insurances for up to a year. However, the number 2 for February was quite easily made into an eight which extended my insurance with six months. The other number 2 on the side slip got "blurred in the rain".

The COMESA is the insurance to have in East and Northeast Africa. It is valid in Burundi, Congo, DRC, Djibouti, Egypt, Ertirea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Malawi, Rwanda, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. When entering the first of these countries you must buy a separate insurance for the first country and then add the COMESA for the rest. I'm not sure why but it is no big deal. Once you've got the COMESA you are set for a large area and a long time. When I bought my COMESA insurance at the border between Malawi and Tanzania I negotiated heavily and managed to get six months for 100 USD. I had bought separate insurances for Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi before I was offered the COMESA at the Tanzanian border.

In Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland I was never asked for insurance and didn't buy any.

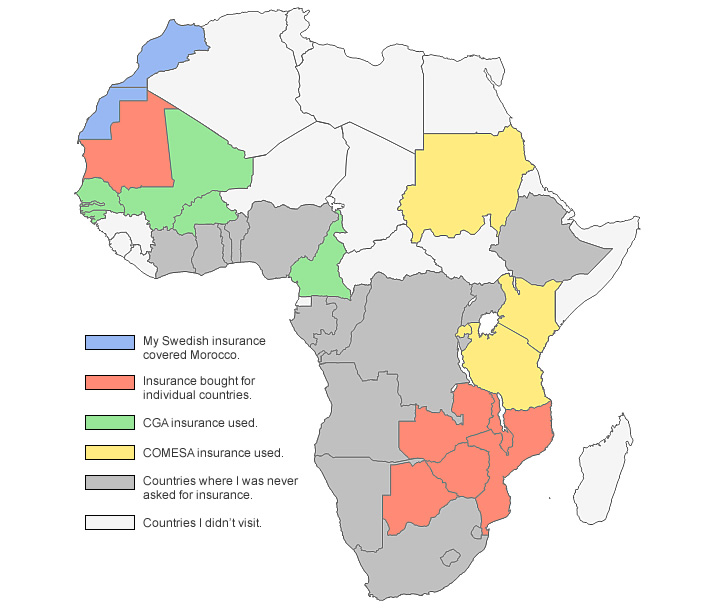

The map below shows in which countries the CGA and the COMESA insurances are valid. Note that there may be other insurances that cover different countries. These are the two main insurances I used.

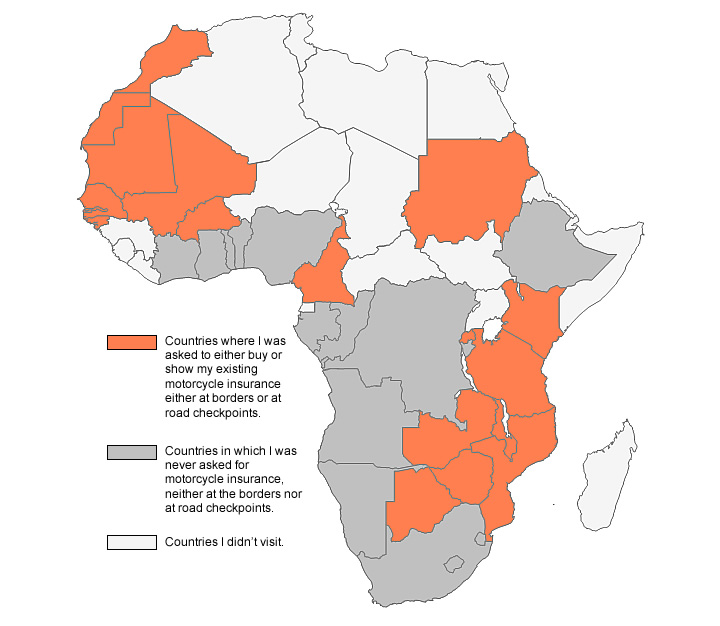

The map below shows in which countries (marked in red) I was required to have motorcycle insurance. I was either told to buy insurance at the border or I had to show that I had insurance either at borders or at road checkpoints. In the dark grey countries I was never asked for motorcycle insurance, neither at borders nor at road checkpoints. This doesn't necessarily mean that insurance is not required, it only means that I was never asked for it.

The map below shows my own experience.

- My Swedish insurance covered Morocco, including West Sahara.

- In red countries I paid for separate insurances per country. Some of the countries in the southeast could possibly have been covered by the COMESA If I would have known.

- In green countries I actually used the CGA insurance.

- In yellow countries I actually used the COMESA insurance.

- In dark grey countries I was never asked for insurance.

- I didn't visit light grey countries.

To top of the page

|

|

|

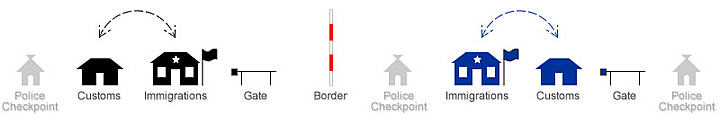

No two border crossings are the same but a typical border crossing looks like this:

Sometimes, but far from always, there is a some distance before the border. Here they will ask you for your passport and perhaps the motorcycle registration document. The details will be noted down in a ledger.

If there is no police checkpoint, the exiting is normally the first stop at a border crossing but it does vary. (Sometimes immigration is first.) This may be clearly marked by a rope, chain, bar or chicane across the road. At other times there is no noticeable obstacle and you will have to look for a building or a hut or a thatched roof by the side of the road. Any person in a border area will direct you if asked. It will be called “douane” in French speaking countries.

This is where you leave your TIP or getting your carnet stamped out. It is fairly important that you make sure not to miss this, especially if you have a carnet. Many times you can’t miss it and you will not be let through without passing through customs but at small borders customs can be difficult to find and nobody will bother making sure you pay a visit. If you do neither have a TIP or a carnet there is no need to visit the exiting customs if you are not told to.

Next up is the which many times is just called “police” in French speaking countries. Often, people are not familiar with the word “immigrations” In that case try asking for “police” or where you get your passport stamped. It may or may not be marked with some form of obstacle. Immigrations and customs may be housed in the same building, they may be on opposite sides of the road or they may be several kilometers apart. The immigrations is where you get your passport stamped out. Getting the exit stamp in your passport is mandatory as you may not be let into the next country without it.

At large border crossings there is usually a to pass before you are allowed to exit a country. In that case a police man will check that your passport has the exit stamp.

Then you pass into no-mans-land. This may consist of a bridge, 20 meters of bad road or several kilometers of bad road. The actual border line may be Indiscernible.

Entering a country you generally visit immigrations first but it may vary. At you get your entry stamp in the passport. Super important! It is your obligation to make sure you get your passport stamped. It is possible to miss it.

At you get your carnet stamped at no cost. If you do not have a carnet, in most countries you will have to purchase a Temporary Import Permit (TIP), which in French speaking countries is called either Passavant or Laissez Passer. This is generally a painless procedure and with a few exceptions, it doesn't cost very much.

Before being let into a country you will pass by a where your documents are checked. At small border crossings there might be no gate.

In some countries there is one or several just after the border. They only want to see your documents.

At some borders you may be given a "Border Pass" when entering the border area. It can be called by different names but it is usually a small slip of paper on which the different authorities you must visit put a stamp or scribble a signature. When exiting the border area you return the border pass at the last gate as proof that you have visited all authorities.

In South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland a TIP is not required and crossing the borders should be free of cost. SA, Lesotho, Swaziland, Namibia and Botswana are visa exempt for most westerners.

There are a lot of horror stories about African border crossings on internet forums and in travel stories but do not despair. Really difficult border crossings are few, most will give you no trouble at all. In West Africa you may be asked for a “small gift” to get your passport stamped but a stern refusal or demanding an official receipt will quickly make these requests go away. In South and East Africa border crossings are generally very straight forward.

At some borders there are a horde of unofficial youngsters hanging about wanting to “help” you through the border. Let’s split them into two categories: Fixers and Scammers.

A can actually be quite helpful. They may get you the forms to fill out and help you with language difficulties, direct you to the right place or change your money. If they really make my border crossing easier I don’t mind giving them a small tip, about Euro depending on the amount of help given. If changing money, a tip is not needed as the poor exchange rate will make up for this. A true fixer rarely expects unreasonably payment for his services.

are a completely different matter. Scammers are a pest that should be treated as the scum they are. I have no contempt for them whatsoever. They can however be quite intimidating and dealing with them is never a pleasant experience. Some people prefer playing their costly game and no one can really condemn them. We are all different as persons and it is up to each individual to chose his/hers strategy. Paying these pests do however justify their existence.

The scammers usually hang around the customs building, in the country you are about to enter, trying to make you pay too much for the TIP or even getting you to pay to get your carnet stamped. These sums can amount to several hundred Euros in bad cases. The scammers will throw any threat at you. That new rules are in place since last month is a very common one as are threats about mandatory escorts needed to cross to the next city. They can sound very authentic but the sheer existence of scammers is a certain sign that you should believe nothing you hear. The problem is, if scammers are allowed to be in the border area, the officials are also in on the scam and there is little help to seek from them.

Notoriously difficult borders:

- Morocco-Mauritania at Guarguarat border post (only southbound as it is the TIP to Mauritania where the scammers strike)

- Mauritania-Senegal at Diama and especially Rosso border posts (in both directions)

Scammers and extortion methods are fortunately rare. Something much more frequent, both at border crossings and at checkpoints within countries, are “”. Many times the immigration officer stamping your passport will indicate, more or less clearly, that he expect a small gift in exchange. A typical sign of this is that they will hold on to your passport longer than necessary, flipping through the pages back and forth. I usually just wait until they get bored and give me back my passport. (They get bored really quick). The classic solution is otherwise to demand an official receipt which usually settles the situation. These encounters often takes no more than a minute but in rare cases I have had to wait up to ten minutes, a breeze compared to the above mentioned scammers.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

In most African countries there are checkpoints along the roads. These can be staffed by various authorities such as the police, customs, military, etc. Sometimes the different authorities have checkpoints within sight of each other. There can also be local community checkpoints and road toll checkpoints.

In the majority of the cases foreign motorcyclists are just waved through without having to stop but inevitably you will be stopped and in certain countries you will have to stop at all checkpoints, most notably West Sahara and Mauritania. Normally the officials at road checkpoints act correctly and politely but there are exceptions. More often than not a big motorcycle will be stopped only because the officials want to have a look and ask a few questions about it. At other times they want to check one, some or all of your documents; driving license, motorcycle registration document, passport, motorcycle insurance.

At rare occasions the officials will hold on to your documents longer than necessary, next they will start talking about being friends which inevitably will lead to a request for a "small gift". Many times they will not pursue the issue very far but occasionally they will. One time in Gambia I was asked in all seriousness why I had not brought the police man breakfast. Que?

A community checkpoint is staffed with civil personnel and usually consists of a rope across the road. They usually charge trucks and taxis a small tax. Motorcycles are just waived through. I don't even make an attempt to stop, only slowing down so they can lower the rope or I can get through the cones.

It is very rare that motorcycles are charged road toll. There is usually a narrow lane around the toll booths especially for motorcycles. On "modern" highways motorcycles may have to pay.

I usually maintain a neutral position until I have determined which way the conversation is going. If the officials just want to lighten up their day with some bike talk, I just enjoy the conversation. If the conversation is going towards "small gift", I take on an overly stern attitude and treat them as the scum they are. I stare them in the eye and wait until they return my documents. This normally happens within a couple of minutes but at times I have waited up to ten minutes. Sooner or later they do return the documents without any gifts.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

I travel with two bank cards (without credit), one VISA card and one Master Card. I mainly use them to withdraw cash from ATM's which is readily available throughout Africa with a few exceptions, Sudan being one. Having two different cards is beneficial in several ways. First of all, one may be accepted while the other is not. In Africa VISA is usually accepted at most ATM's that take international cards (not all do). MC is also widely accepted but not everywhere. Secondly, some countries have only small denomination bills and there is a limit to how many bills that can be dispensed from an ATM at each withdrawal. Some banks will automatically lock bank cards if too many withdrawals are made in one day in "suspicious" countries. Having your bank card locked can be a major hassle. The bank may have to issue a new card which will not easily reach the card holder in a remote place. By having two cards, linked to separate bank accounts, you can withdraw more money at one time without risking automatic card locking.

I carry both USD and Euro as backup cash. US dollar is by far the most useful currency in Africa. Euro and GBP are also widely accepted. However, some payments can only (without exception) be made in US dollars, notably some visa fees. There is really no reason to carry Euros or GBP as long as you have USD.

In some countries it is very difficult to obtain foreign currencies. Ethiopia and Sudan are examples but there may be others.

I didn't really have any need to replenish my emergency cash until I reached East Africa. Before that (in West and Southern Africa) I used my emergency cash very little.

In it was possible to withdraw US dollars from one of the ATM's (a green one if I remember correctly) just outside the central Nakumatt Supermarket and the popular Bourbon Café (S1° 56.731' E30° 03.691').

In I could easily change Ethiopian Birr to US dollars on the black market housed in tiny sales stands along the Ras Desta Damtew Street (N9° 00.961' E38° 45.348').

that there are no ATM's that accept foreign bank cards in Sudan.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Poring over an Africa map, the possibilities seem endless but unfortunately there are many bureaucratic and political obstacles that prevent the imagination from wandering freely. This map gives a rough picture of the current (as of indicated date) situation to the best of my knowledge.

The Ebola epidemic that was at its' height when I passed through West Africa in late 2014, early 2015 is officially over since the beginning of 2016. It should now be safe traveling htrough those countries (Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia).

To top of the page

|

|

| |

To get a rough picture about how far a journey from top to bottom or the whole way around Africa would be, have a look at this map. I have indicated in green text the total distance I traveled in 5 000 km increments. It'll give a rough estimate for planning purposes.

Traveling time is highly individual. One can travel from Morocco to Cape Town in a few months or one can take forever. On the same map is indicated in turquoise where a month was added to my journey. I would say my speed of traveling is on the slow side of the scale.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

For general route planning I use the trusted Michelin maps well known to most African overlanders.

- 742 Morocco

- 741 Africa North & West

- 746 Africa Central & South

- 745 Africa North East, Arabia

Be aware that any white road on these maps will most likely be small dirt roads or even single track trails and are most of the time demanding to say the least. But they can also be a lot of fun.

A GPS is indispensable, especially when entering big cities. If I have marked my destination I will always find it without much hassle. When traveling on small tracks the map might not show the tracks correctly but it will show whether I'm heading in the right direction. A great map source for a GPS is the Open Street Map openstreetmap.org. It is a free source and it is as detailed as most other GPS maps. The: garmin.openstreetmap.nl is an excellent site to download Open Street Maps for free. Here you can select countries or areas of your choice.

Tracks4Africa is another popular resource for GPS maps.

The coverage is not very good in West Africa but many hard core off-roaders use it in South and East Africa.

To top of the page

|

|

| |

Speed traps are a rarity in Africa. Road conditions usually render them useless as you can't drive at the permitted speed anyway and most of the time you don't know what the maximum speed is and nobody will be able to tell you. When passing through villages and towns there is usually a speed limit of 40-60 km/h accompanied by road bumps the size of the Pyrenees.

However, there is sneaky police at some places in Morocco, usually at spots where they are likely to be successful, so if you have a "speeding feeling", trust it. Don't be overly worried though, even in Morocco the speed traps are few.

In West Sahara the speed guns are primarily in use at gas stations (the only place where there is a bit of shade). Someone who had lived in Dhakla for many years told me that the police use the speed guns at gas stations because people stop at these stations to have a drink or two and then pull out like no one is coming (and believe me, they are perfectly right thinking so), but apparently there have been some accidents because of this so the police think it is the people speeding that is at fault.

I saw a speed gun in the hand of a police officer in Ghana but I'm not sure he knew how to use it.

To top of the page

|

|

|