Continued from previous post. Accompanying map.

I awoke in my tent that was pitched on a secluded spot in the village of Ganse in the northeastern part of Ivory Coast. I could hear the women sweeping the ground in front of their houses, a sound that is heard every morning in every village all over Africa.

Soon I was conferring with two of the villagers about the chances of getting my motorcycle across the river. Quite predictably they said it could be done. In places like this people are used to solving all kinds of problems themselves because there is no assistance that can be called upon. People have to manage by themselves or be left without.

Before I drove down the river bank I had the five men that had been assembled for the task, assisting me in doing a test lift of the bike, relieved of all luggage. That meant a bit over 200 kg in total and 40 kg per man. It was no problem lifting it off the ground. The locals had probably never heard about such a silly thing as a test lift. They knew it would be manageable to get the bike into one of the canoes but this is not just any local bike that can be replaced in the next city. This is my bike, my trusted bike that has no replacement.

Getting it into the canoe was a bit trickier as six people had to find a space to stand and somewhere to get a grip which allowed them to contribute to the communal force. It just barely fitted in between two of the seats which kept it jammed into a steady position, but it was big and tall and seemed to lean over the side of the canoe. We all had to sit on the opposite side to counterbalance the weight.

John, the man from Ghana that spoke English, asked me if I was nervous and assured me that I had no reason to be. He probably thought I was nervous about falling into the river and drown as many Africans don’t know how to swim. I had no worries for myself as a short swim to the shore in the calm water wouldn’t present any problems unless a hippo decided to interfere. It was of course the bike I was nervous about. The river was ten meters deep and if the canoe flipped over my bike would be gone forever. People may be resourceful in remote areas like this but there is a limit to their ingeniousness.

It only took a couple of minutes to paddle across the river and it was a steady crossing but I think I held my breath the whole time. It was a big relief when the canoe touched solid ground on the opposite shore. There, we lifted the bike out of the canoe, turned it uphill and loaded the luggage.

It was also a relief as my possibilities to go further into the country opened up. If I had had to turn back I would be limited to the border area as there aren’t any bridges over the Comoé River until much further south. Actually I crossed the next bridge on my way out of the country. I still had to get out of this remote area but I had at least some kind of a road ahead of me, if not a very good one. I said goodbye to the people that had helped me across the river and took off.

It was a wonderful morning with birds singing in the trees and the relatively cool morning air made the ride as relatively comfortable. There was still a lot of sand to navigate and ruts to balance through. My arms were still aching from yesterdays´ driving.

At one point I met two young boys on the road, perhaps seven or eight years old. One of them was walking close to the wheel track I was following and as it is difficult to go outside of the chosen wheel track I came very close to him. He was barefoot and wore a pair of shorts and a T-shirt, both incredibly dirty. As I was heading straight towards him, he got scared out of his senses. He threw the puppy dog he was carrying up in the air and fled head over heels into the bushes. Poor boy. I felt so sorry for him.

Part of the reason for choosing small roads was to avoid the police checkpoints as my papers only allowed me to travel from one border post to the next, now I was heading straight into the country. After two hours, about half way to Dabakala, I met two armed policemen on a motorcycle. We stopped and greeted. They asked me a few general questions about where I came from this morning and where I was heading but they asked for no documents. I guess out here in the bush, paperwork has less importance. In a village a bit further down the road I met a police pickup truck and the same procedure took place.

At a police post just before Dabakala I was neither asked for any papers but they told me that the road between Dabakala and Katiola was paved. What a nice surprise! I had calculated with another very long and tiresome day on endless dirt tracks but now I was at the edge of the asphalt, like if these policemen were genies giving me three wishes. I asked for nice and smooth asphalt on all three wishes and nice and smooth asphalt I got. What an unexpected turn of events. Instead of reaching Katiola at sunset as a total wreck, I was now cruising down the road looking forward to an early arrival.

Katiola was an unattractive town. The hotel I stayed at was nice but extremely mismanaged so I made an early departure the following day. It was a short day’s drive to Yamoussoukro, or Yakro as it is called, the administrative capital of Ivory Coast. The road was very treacherous, This is one of the main thoroughfares for goods that is transported from the coast to the landlocked countries of Mali and Burkina Faso and therefore it was heavily trafficked by large, overloaded trucks. The potholes in the road were large and deep. If I would have hit the sharp, far edge of one of these holes I would have gone flying. Especially dangerous was it when overtaking trucks as I had to be close behind and a pothole could appear underneath the truck very suddenly. The best option was to drive in line with one of the wheels of the vehicle in front as it will try to avoid the holes in the road.

Before I reached Yamoussoukro I was stopped at a police checkpoint. It consisted of two policemen by a small bamboo roof. I had passed numerous checkpoints during the day but none of them had stopped me. Not that I had looked too closely for any hand signals. At this checkpoint the hand signals could not be mistaken.

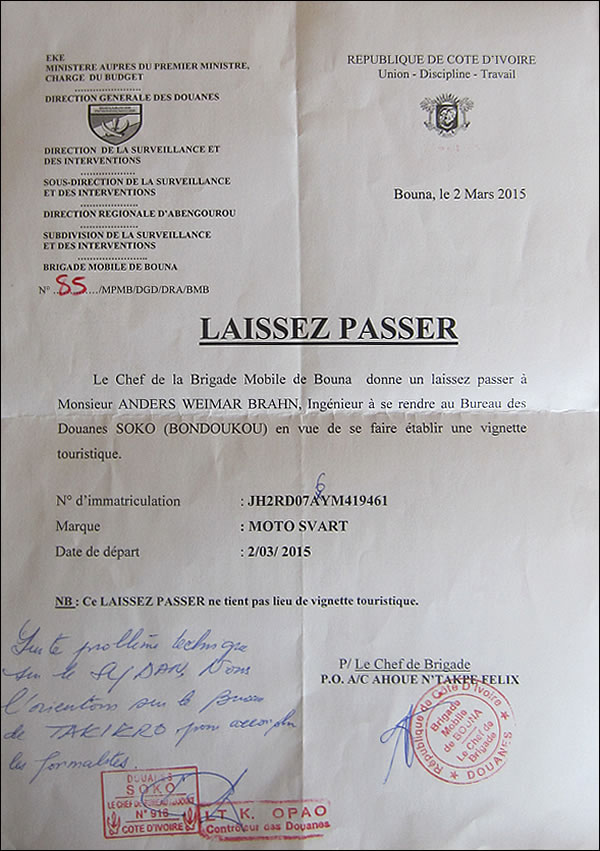

I soon understood the intentions of these cops as they started to gather a number of documents, or hostages, from me. The first document I handed over was the restricted Laissez Passer that only allowed me to travel from the border post of Bouna to the border post of Soko and, according to an addition, to the border post of Takriko, all on the Ghanaian border. I was now smack in the center of the country. This is where the policemen had their real and only chance to get me but to my surprise the officer only seemed to notice the words “Laissez Passer” in fat, printed letters and perhaps the official stamps. He didn’t bother to read the fine print or the handwritten note.

He stacked it together with my driving license and registration document, booth copies, and held on to them. This told me three things: He did not intend to return my documents without asking for a “small gift”, he did not know that he held the key to this “small gift” right in his hand in form of the Laissez Passer that didn’t allow me to be here, and I knew that I would leave this police checkpoint without paying a single CFA.

The policemen spoke a little English but only enough to communicate their message. I used this to my advantage. After holding on to my documents for long enough in order for me to realize that he wouldn’t give them back without something in return, he started with indicating that we were now friends and therefore I should give him 10 000 CFA (15 €). I put on my most confident face and told him very clearly that we were not at all friends. We just met a few minutes ago and besides, my friends don’t ask me for petty gifts. He continued his attempt but I stared him straight in the eyes until he weakened and returned my documents. I didn’t thank him or say good bye. I just left. The whole process took about ten minutes.

The only time my restricted Laissez Passer was scrutinized and questioned was at a police checkpoint when I was driving towards the border at Niablé. This was 130 km to the south of Takikro, the border post I was directed to on the document. The police officer noted this and questioned it with emphasis. I told him quite truthfully that I had tried to get the correct document at several border posts but they had not been able to issue it for me. This policeman didn’t know I had been doing a tour into the country. In his view I was not far outside my permitted route and I was heading for the border, so he let me go.

I guess officers closer to the borders are more knowledgeable and observant to this type of documents. A junior customs officer at the border also questioned why I was at this border when the paperwork said I only had permission to go to Takikro but the senior officer just waved me through.

Yamoussoukro is one of a number of “artificial” capitals in the world. Normally it is the largest or at least one of the most prominent cities in a country that is the capital. In Ivory Coast, the big city of Abidjan by the coast used to be both administrative, economical, legislative and factual capital. The administrative part was moved to Yakro in 1996 by Félix Houphouët-Boigny the first president of Ivory Coast. Yakro happened to be his home town. Houphouët-Boigny was president from independence in 1960 to his death in 1993. When he decided to move the capital to his home town, he also initiated a number of rather lavish construction projects. One of them was the gigantic Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro. This is a remarkable building in many ways. It is 158 meters tall, a notch taller than St Peter’s cathedral in Rome and it seats 7 000 visitors but can hold up to 18 000 inside it’s’ walls. It is built on a, what I estimate to be, 2 square kilometer piece of land, not in the center of the city but on the outskirts, just on the edge of the jungle.

But it’s most striking feature is the 7 000 square meters of stained glass around the circular central structure. These were made by three French companies and shipped here. Tonnes and tonnes of marble were imported from Italy, Spain and Portugal. The largest pillars inside are not supportive but houses four elevators and six staircases up to a balcony some 35 meters above the floor. Drainage pipes are led through the remaining two pillars.

There is an underground chapel below the main altar, a sound system is built into the four pillars around the altar and conditioned air is flowing up though the floor and into the semicircular rows of benches but this is only turned on at Sunday mass which typically draws a crowd of 700. The kilometer long main approach to the cathedral can be lit up into a fantastic view but due to cost restrictions this is only done for fifteen minutes at Christmas Eve.

All these remarkable facts fade into insignificance when compared to the fact that the complete cathedral plus a catholic hospital just to the side of it and a planned university on the opposite side were financed by the president himself as a ”gift” to the people of Ivory Coast. If he was able to pay for such a large construction project straight out of his own pocket, he must have gained an incredible fortune during his lifetime. No one can be ignorant to where that fortune came from and as his life was coming to an end (he died three years after completion of the cathedral) it was not much of a sacrifice. When he was asked how much the cathedral had cost he answered that: “If you get a gift, you don’t ask what it cost.” According to Wikipedia the total cost for the basilica was US$300 million. Guinness World Records lists it as the largest church in the world.

/AB

|